Verizon’s 2020 Cyber-Espionage Report (CER) draws from seven years of Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) content, and more than 14 years of Verizon Threat Research Advisory Center (VTRAC) Cyber-Espionage data breach response expertise. The CER serves as a guide for cybersecurity professionals looking to bolster their organization’s cyber defense and posture and incident response (IR) capabilities against cyberattacks.

Cyber-Espionage threat actors pose a unique challenge to cyberdefenders and incident responders. Through advanced techniques and a specific focus, these threat actors seek to swiftly and stealthily gain access to heavily defended environments. Depending on their goals, they move laterally through the network, obtain targeted access and data, and exit without being detected. Or, they stay back and maintain covert persistence.

Threat actors conducting espionage can include nation states (or state-affiliated entities), business competitors and, in some cases, organized criminal groups. Their targets are both the public sector (governments) and private sector (corporations). They seek national secrets, intellectual property and sensitive information for reasons that include national security, political positioning and economic competitive advantage. The Cyber-Espionage threat actor modus operandi includes gaining unauthorized access, maintaining a low (or no) profile and compromising sensitive assets and data. Technology makes espionage actors fast, efficient, evasive and difficult to attribute. In a nutshell, for the threat actor, Cyber-Espionage is an opportunity with relatively low risk (of being discovered), low cost (in terms of resources) and high potential (for payoff).

According to the report, when it comes to the overall most prevalent types of breaches for the 2014–2020 DBIR time frame, Cyber-Espionage ranks sixth (10%), and Privilege Misuse ranked fourth at 11% for example. Because Cyber-Espionage is a difficult incident pattern to detect, the numbers may be much higher, according to Verizon. The kinds of data stolen in Cyber-Espionage breaches (e.g., Secrets, Internal or Classified) may not fall under the data types that trigger reporting requirements under many laws or regulatory requirements.

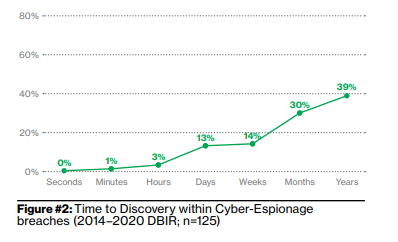

In the 2014–2020 DBIR time frame, for Cyber-Espionage threat actors, the Time-to-Compromise ranges from mere seconds to days, while the Time-to-Exfiltration ranges from minutes to weeks. For cyberdefenders, the Time-to-Discovery for Cyber-Espionage breaches is months to years and the Time-to-Containment ranges from hours to weeks. The slow, methodical and lengthy process that threat actors employ speaks to the patience and complexity often accompanying Cyber-Espionage attacks. It is indicative of the threat actor’s due diligence in understanding the target’s environment and cybersecurity posture, and in leveraging that knowledge to accomplish their objectives without detection.

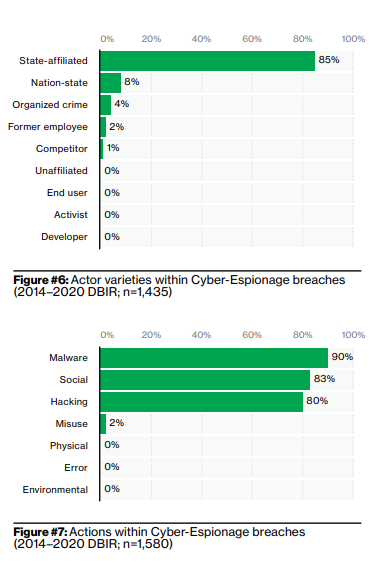

The top actor varieties in Cyber-Espionage breaches over the past seven years, according to the report, are State-affiliated (85%), Nation-state (8%), Organized crime (4%) and Former employee (2%).

Within the “all breaches dataset” (which includes cyber-espionage as well as other types of breaches), for a financial motive is overwhelmingly the threat actor’s motive (86%).

For Cyber Espionage breaches, the top Actions, according to the report, are Malware (90%), Social (83%) and Hacking (80%). For all breaches, the top Actions are Hacking (56%), Malware (39%) and Social (29%). This implies more of a reliance on Malware and Social actions for Cyber-Espionage threat actors than for all breach threat actors.