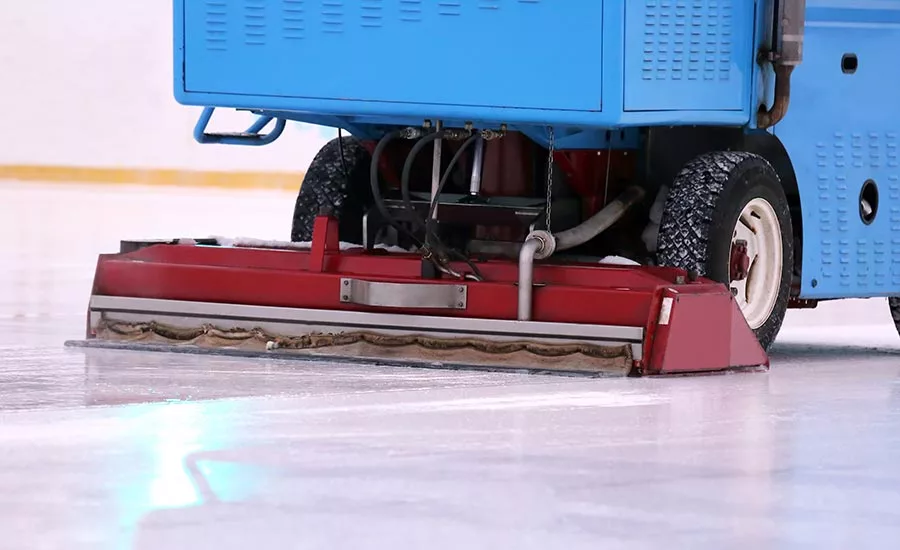

Driving the leadership Zamboni

After 14 years of finding last-minute goalies, securing locker room doors, and trying to parcel out equal ice time to the skaters, I recently shed the captain’s “C” from the jersey of my recreational hockey team. Like many security professionals, I gravitate to leadership positions. But true leaders know when to step aside. And they understand that the most important thing they can do is to create a pathway for new and aspiring leaders to take their place. With my hockey teammates, I realized I was doing them a disservice. As other life responsibilities increased, my interest waned in managing late-night ice times and questioning penalty calls by refs. In fact, one of the assistant captains had quietly stepped up to take on duties that I was too busy to handle, such as figuring out player payments and ordering new uniforms. It was both an obligation and honor to tap him as my successor. And it was my duty to clear a path for him: serve as a human Zamboni — the machine that smooths the ice — so to speak.

Unfortunately, many leaders stick around past their expiration date. They see leadership as a status symbol or mark of accomplishment — something to be seized and held at all costs. Remember that expression, “Old leaders never die, they just fade away”? Leaders should be like photographers: they never die, they just develop new talent.

Karen Frank, CSO of Pratt and Whitney, credits her CSO at Caterpillar, Tim Williams, with spotting her potential and developing her as a leader and strategist. Frank serves on the Advisory Council of ASIS’s CSO Center for Leadership & Development, an organization of which Williams was a principal architect. Jeff Karpovich of High Point University, a Security magazine Most Influential People in Security honoree, promotes his captains and majors from the ranks of the school’s security guards.

In fact, you can judge how effective a leader has been by how his protégés are doing. Consider NFL coaches Bill Walsh and Bill Parcells. Between them, they hired at least 30 assistants who later became head coaches, many of whom won Super Bowls. Though not as storied, the security world has its own analogues. Stevan Bernard, formerly EVP at Sony Pictures Entertainment, mentored Marcelo Rodriguez (now VP at Assurant) and Paul Kennedy (SVP at Caesars Entertainment Corporation).

The healthiest family trees have multiple branches and deep roots. While at Baker Hughes, Russ Cancilla mentored both Brian Hogan, now head of corporate security at Amazon, and Joe Olivarez, now CSO at Jacobs. Olivarez recalls that his boss developed him from an operations-level investigations specialist into a well-rounded executive who understood the company’s business and could communicate at a high level and influence business executives. “These are people who are themselves influencers. They don’t have to listen to you,” Olivarez says. He paid it forward by developing Joe Walters, who took the top role at NRG Energy, even bringing Walters in as a co-instructor in a security master’s program that Olivarez was teaching at the University of Houston. The list goes on.

Yet some security leaders consulted for this column demurred when asked how their boss handled their development. In some cases, deputies felt suppressed rather than encouraged, opting to take a CSO role elsewhere where they could shine. Those professionals may have departed eventually anyway, but a confident security executive should never stunt the growth of a direct report. In fact, it is in the best interests of the organization for them to hire and refine staff with skills and talents both complementary and superior to their own. Why? For succession planning purposes, of course, but also because security executives should be focused on strategy, vision, motivation, talent management and other 50,000-foot issues, leaving important day-to-day work to their reports. Moreover, confident bosses seek highly gifted staff to challenge their assumptions, raise competing arguments, help decide thorny issues, and otherwise sharpen their thinking. And speaking of sharpening, now that you’ve piloted the Zamboni and cleared a smooth path, let’s get your direct reports laced up and out on the ice.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!