Security Risk Management in Maryland's Seaports

How David Espie, Director of Security, secures Mayland's Seaports.

On the landside, the MPA has been leveraging advanced keying technology for access control for the Port. Centralization has been a major enhancement there.

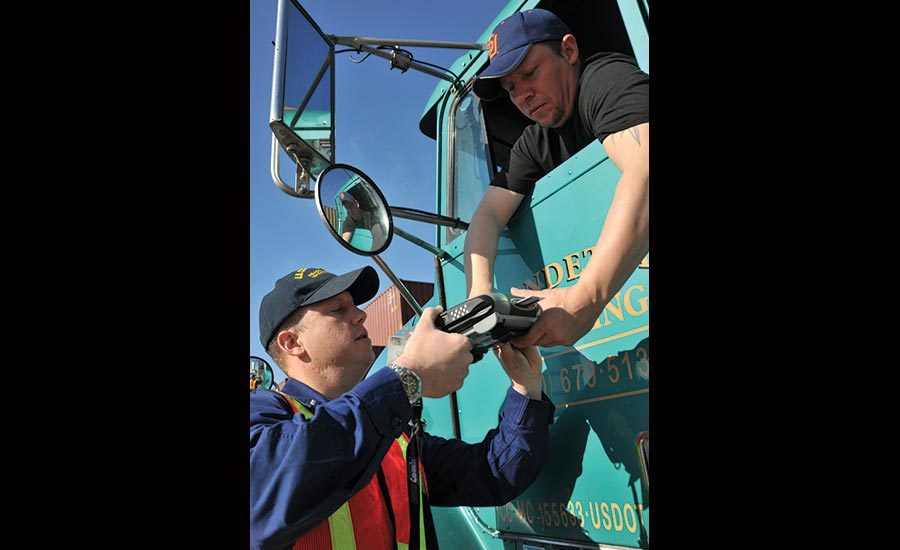

Photo courtesy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

In addition to the federal Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC), Maryland ports require a secondary credential in the form of the MPA ID badge for all facility employees, including contractors who have a legitimate business need to enter unescorted on property owned and controlled by the MPA.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

“It’s its own city. We have a large population. We have numerous access, entry and exit points. We have highways. We have equipment that is operated to facilitate the movement of commerce throughout the port,” says David Espie, Director of Security for the Maryland Port Administration. “We have both a land-side threat and we also have a waterside-based threat. It could be an active shooter. It could be domestic or international terrorism threat. It could be anything.”

Photo courtesy of David Espie.

If the Maryland Port Administration (MPA) is practically a city, Director of Security David Espie is arguably the chief of police.

It is a reasonable analogy. The port operation is vast, overseeing six state-owned marine terminals comprising about 1,000 acres. They run 24/7 and an average weekday sees up to 4,000 entries and exits, with several billion dollars’ worth of cargo in play at any given time. There are tenants, vendors and contractors coming and going. The International Longshoremen Association alone supplies 1,600 personnel.

Espie’s office boasts a healthy $12 million annual budget. Add in the Federal Port Security Grant Program, a police detachment and 80 security officers from Allied Universal and the total security spend creeps near $24 million a year.

“It’s its own city. We have a large population. We have numerous access, entry and exit points. We have highways. We have equipment that is operated to facilitate the movement of commerce throughout the port,” says Espie, who has headed up port security since 2011. As in any city, there are security concerns. “We have both a land-side threat and we also have a waterside-based threat. It could be an active shooter. It could be domestic or international terrorism threat. It could be anything.”

Espie’s main job is not just to protect physical infrastructure but to facilitate commerce. He is there to ensure the steady flow of goods: the Port of Baltimore alone handled more than 38 tons of cargo a year at last count, valued at almost $54 billion. “The Port continues to be one of Maryland’s leading economic engines and our administration congratulates everyone who had a role in this well-deserved recognition,” Gov. Larry Hogan says in recognition of the port’s ninth consecutive “Excellent” rating on the Coast Guard Security Assessment.

Here is how Espie makes it all work.

Force Multiplier

Espie brings a number of tools to bear to ensure security across this dynamic landscape. Most recently, he has been implementing a combination of security video and video analytics as a force multiplier. Analytics leverages artificial intelligence to interpret and flag suspicious activity in real time. “It gives the camera some brains,” he says. “It goes beyond video to do human-like work. It can alert you to abnormal behavior in a way that you otherwise would not be able to do.”

He leverages the analytics at his largest terminal specifically to watch people crossing from the water onto the land. “It’s like having police patrol that supplements our routine police activity,” he says. “We had a case of an individual docking at one of our berths where they had no port business. They were actually having some non-criminal type of engagement, but contact made with them by the police yielded a person with an active criminal warrant.” Without analytics on the beat, they might have slipped by unnoticed.

On the landside, Espie has been leveraging advanced keying technology for access control. Centralization has been a major enhancement there. “A person can basically sit at one station and monitor multiple systems, instead of having to go to the various systems and perform checks to see if there are any alerts or alarms,” he says. “It’s a much more orchestrated and manageable means to monitor these varied systems.”

While the gadgetry has been a boon, Espie says his most effective tactic for managing the port’s extensive security footprint is good old-fashioned conversation.

“The number one priority that I have in deploying our security plan is communication, whether it’s verbal communication, meetings, seminars or briefings. I do not support the sending of emails within my office. I make my folks get up and go talk to each other,” he says.

Beyond daily staff meetings, he also engages in routine dialogue with the police and security forces that augment his core team. “The police department, fortunately, is right down the hall. In regards to the guard force, we have moved the onsite manager and assistant manager to within our building, specifically to facilitate face-to-face communication,” he says.

As a public sector operation, Espie needs to communicate not just laterally – to his direct reports and supporting security teams – but also up the chain of state government. He is answerable to the Secretary of Transportation and his efforts can also be micro-managed by eager state legislators and others.

“I’ve seen that throughout the United States, where various directors have that issue. I’m on the American Association of Port Authority Security Committee, so I’m able to meet twice a year with anywhere from 25 to 200 port security directors. Yes, I’ve heard a lot of stories where they have been restricted, or they do not go forward because they’re not going to get the support,” he says.

This is where good communications pay off. “I have never encountered that issue here. As long as I prepare my reports or suggestions in a very thorough and thoughtful, well-searched way, I have always had them well-received and very much appreciated,” he says.

The backing of state and local leaders has proved helpful when Espie has launched major security initiatives, as for instance the introduction of the Maryland Port Administration Terminal ID Badge.

Granular Security

In addition to the federal Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC), Maryland ports require a secondary credential in the form of the MPA ID badge for all facility employees, including contractors who have a legitimate business need to enter unescorted on property owned and controlled by the MPA.

“We’re one of the few ports in the United States that utilizes a secondary form of ID, in addition to a driver’s license,” Espie says. The programmable badge allows a granular level of access control. “We are able to segregate our terminals, basically compartmentalize them to where only certain employees have access to certain terminals based on their purpose and business needs. I’m sure we’re one of the very few ports in the United States that has that compartmentalization.”

This high degree of refinement helps to make security personnel more effective and efficient by quickly and easily validating roles for the many hundreds of individuals who may be in movement at any given time.

“It says not only are you supposed to be here, but within the ‘here’ you are supposed to be only here,” Espie says. “The badge also identifies your affiliation, whether you’re an employee, a tenant, a contractor. Now police are doing a patrol, and they find a contractor or vendor in an area where they most likely they have no reason to be. That would raise a security flag for sure.”

While the MPA badge has helped Espie to tame the physical security situation, another front has lately opened up. Increasingly, port security comes with a cyber component.

“The cybersecurity concern has grown dramatically,” he says. “We basically run the port, so from an operational standpoint our computer systems obviously need to be secure and free of phishing expeditions, denials of service and so forth. Then that’s grown into the responsibility to ensure our tenants engage in cybersecurity. Then if we do have an incident – whether it be within the State of Maryland, or one of our tenants or related entities – we have a huge reporting requirement.”

All this adds up to a substantial administrative responsibility, over and above the many tasks related to physical security.

“The tenants are clearly aware that I’m the port facility security officer and that we have a cyber mandate, myself and staff. Any time we have any kind of contact or meetings, we will touch upon cybersecurity to reaffirm that point of how important it is,” he says.

He has backup in this function, in the form of a Maryland Port Administration quality action team that coordinates cyber activity among tenants and stakeholders. The Maryland Department of Transportation IT department likewise supports the security team in this regard, bringing best practices to the table, along with several federal port security grants related to cyber. “I think that we are very far ahead in terms of a lot of ports in the United States. We like to model ourselves after the port of LA. They have a fantastic cybersecurity program. One day we’d like to emulate them totally, but we’re not there yet,” Espie says.

Protected Commerce

At the end of the day, Espie is eyeing a big picture that goes beyond badges and cyber breaches. The end game in port security is not just an absence of negative incidents: it’s the ability to actively foster and support commercial activity.

“We are here to protect commerce, to see that it is not damaged, not vandalized or stolen. When our marketing personnel go to these different vendors – whether it’s Cat or John Deere, Case New Holland, Subaru, Mercedes, BMW – they’re going to know that when their cargo is on our terminals, it’s going to be safe and secure. It’s going to get to the customer the way that it was when it came off the assembly line.”

For port security professionals to reach that high bar, they have to be able to see beyond their own local situation. There are national and international forces in play that can influence port security operations, and as Espie looks to the future, he says he would like to see closer cooperative relationships around the sharing of that critical security information.

“I’m hoping that in the next year and the years to come, that the sharing of intelligence between the federal government and local entities such as a state port like us improves,” he says.

“I want to have any and all potential intelligence as soon as possible so I can make a decision, whether that would help me maybe decide what technology I may want to procure or what other changes I might want to make,” he says. “I’ve been pushing since I’ve been in this position for all directors of security at ports in the United States to have, at a minimum, a secret-level security clearance. We need to know sooner rather than later of any particular threats.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!