Do No Harm: Profiling Evil and Violence in the Workplace

What Dr. Park Dietz wants you to know about mitigating workplace violence, zero tolerance policies, OSHA’s potential legislation and more.

According to Dr. Park Dietz, while lots of companies have crisis management plans that kick into gear in an emergency, many enterprises and their security teams haven’t examined what they could do to head off workplace violence incidents before they begin. “Workplace violence encompasses so much more than the gunman who commits a multiple-victim shooting,” he says. Photo courtesy of Peter Levshin

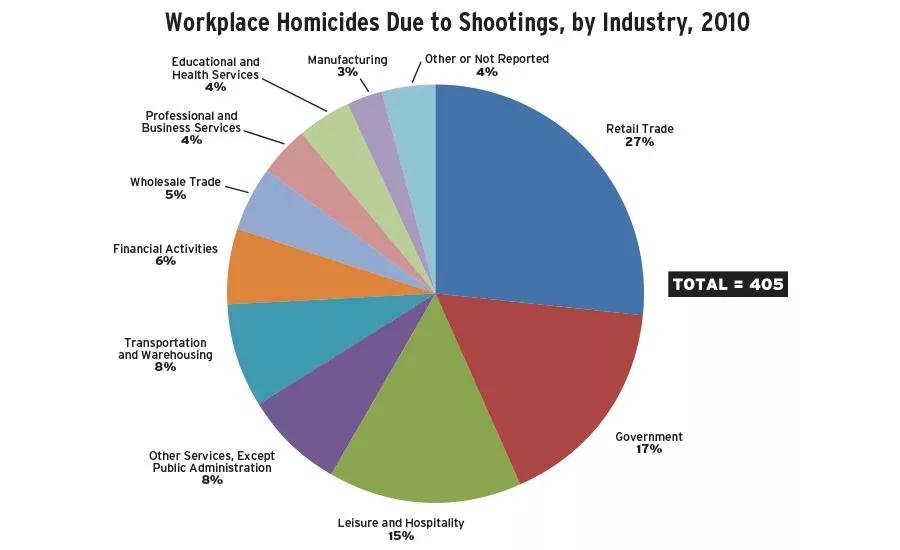

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, shootings accounted for 78 percent of all workplace homicides in 2010 (405 fatal injuries). More than four-fifths (83 percent) occurred in the private sector, while only 17 percent of such shootings occurred in government. Workplace homicides attributed to shootings involving workers in elementary and secondary schools are relatively uncommon, although 12 were reported between 2006 and 2010. Of the 405 workplace shooting victims in 2010, 110 (or 27 percent) occurred in the retail trade industry. About four out of every five workplace homicide victims in 2010 were men. Robbers and other assailants accounted for 72 percent of homicides to men, for example, and only 37 percent of homicides to women. BLS says that a substantial difference exists when relatives and other personal acquaintances are the assailants: only three percent of homicides to men, but 39 percent to women. Assailants with no known personal relationship to their victims accounted for about two-thirds of workplace homicides. Chart courtesy of OSHA

Workplace violence is seldom the freak episode that the media portrays it to be. It rarely involves a mass shooting with a gun, and rarely does it result in a homicide or mass casualty. More often, it’s a threat uttered under an employee’s breath, an intimidating stare, or a domestic violence victim who is being harassed by her spouse at work.

And it’s also something that others suspected, but they just couldn’t quite put two and two together, to gather the courage or enough information to report the behavior to HR or security. After a tragic incident, we often hear the same comments from a perpetrator’s neighbors or friends. “He was a bit strange; he kept to himself; he wasn’t very outgoing…” And more.

But employees who act out in violence often have a history of anger, aggression, feeling cheated, rule-breaking and making others feel uncomfortable. The one incident that gets everybody’s attention is usually preceded by many, smaller episodes that managers and employees may neglect, due to their own workload, not wanting to get involved, or not wanting to accuse an employee of something that he/she hasn’t done or won’t ever do.

Those are the things that Dr. Park Dietz wants you to know about workplace violence.

As one of the world’s foremost forensic psychiatrists, Dr. Dietz has researched workplace violence for more than 30 years, interviewing the perpetrators and examining the causes of workplace events. He is also president of Threat Assessment Group (TAG), a workplace violence training and consulting company, and a forensic psychiatrist for the FBI’s National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime. More recently, he worked for the Department of Justice in the prosecutions of Jared Loughner (who shot Gabby Giffords and five others in Tucson, AZ), John Hinckley Jr., Jeffrey Dahmer, Erik Menendez, Ted Kaczynski, Andrea Yates, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (the Boston Marathon bomber) and Dylann Roof, the man convicted in a church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina.

Dr. Dietz wants enterprise security executives to learn effective violence prevention programs, and he’s advocating an integrated approach to it.

“We need to generate awareness that the concept of workplace violence prevention should not be very narrow and treated separately from such topics as sexual harassment, bullying, insider threat, radicalization or cybercrime,” he says. “There's no need to reinvent the wheel and set up procedures for each of those issues separately. You can instead, be smart about it and have an integrated approach in which all of those are managed by the same group of people who have responsibility for it. Then, you roll out training to the entire organization that integrates all of those topics and more.” Those topics include the FBI definition that workplace violence is “any action that could threaten the safety of an employee, impact an employee’s physical or psychological well-being, or cause damage to company property.” That includes stalking, threats, intimidation, violence as a byproduct of a robbery or other crime, bullying, sexual harassment and domestic violence, but also includes misuse of proprietary information, product tampering, sabotage, extortion, kidnapping, targeting of executives, and other enterprise-wide risks.

One of Dietz’s earliest findings in researching the subject of workplace violence was that shootings, harassing letters or parking lot brawls are never how problems begin. “Thirty years ago when we began to research this field, we found that threats are not the early warning sign we had thought they might be,” he says. “Threats are a very late-stage warning sign in a process that begins with much more diverse forms of misbehavior and misconduct.”

And while many enterprises have crisis management plans that kick into gear in an emergency, many enterprises and their security teams haven’t examined what they could do to head off workplace violence incidents before they begin.

“We want managers and those who are responsible for mitigating this issue to recognize two kinds of behaviors,” he says. “One kind reflects a troubled person, and the task is to get them help before their behavior worsens or they create other problems. The other kind is to recognize what we call ‘troubling situations,’ and these are more obviously related to security concerns. But the essential issue here is that managers know that when unwanted behaviors occur in the workplace, they are not alone in handling it, and they need to be in touch with the professionals within their company, who are typically from security and HR. For the employees the training is even more focused and narrow, and we’re really teaching employees two things. The first is what they need to notice and report to HR or security, and the second is what they should do when they perceive danger.”

What specific and troubling employee behavior should managers and enterprise security directors look for? According to Dr. Dietz, the obvious behaviors are verbal abuse, bullying, intimidation, threats and harassment. Before these arise, Dr. Dietz says, there will typically be uncooperative and non-compliant behaviors, performance problems, a bad attitude and more.

And before these arise, seemingly trivial behaviors that are the earliest signs can include an employee rolling his or her eyes when they’re given an assignment or not reciprocating a “hello” in the hallway. “Of course no one knows how often that occurs,” he says, “but it’s far more common than more serious behaviors and, yet, that’s the level of which one needs to begin to manage behavior.”

But what if you’re wrong in believing a rolling of the eyes means a disgruntled employee? What if it was just a fluke of sorts?

“If lots of warning signs get reported, don’t many of those people end up being harmless people?” asks Dr. Dietz. “And the answer is absolutely. So the way we guard against that causing a problem is by having a process in which we cultivate over-reporting. We do know that most reports will be false positives, and we take great pains not to do anything bad to people who are false positives. So the first step when there is a sighting of possible misconduct of even the lowest level is to look at what’s already available within our documentation to see whether this person has been involved in other problematic behaviors during the period of their employment. Look at their social media to the extent that is publicly available and discretely gather a bit more information about this person. And if all of that checks out negative, that’s the end of it. Some of the time we find red flags in those other sources, and we’re very glad somebody reported it.”

The pre-scientific approach to false alarms, he notes, was for managers to think that they would look weak if they call for assistance. Consequently, what they did was nothing. “The universal problem we encountered is that managers ignore the problem, hoping it will go away. Instead we changed the rules and the expectations so that it becomes the manager’s responsibility to consult security or HR about how to handle it, because we know that security and HR have the capacity to document and to take the right actions. So we advocate taking the decision making out of the hands of the worst managers and putting it in the hands of security and HR.”

Zero Tolerance

The concept of zero-tolerance policies is rooted in politics, and over the last 20 years, the policies have been imported into the criminal justice system, and have spilled over into schools and workplaces and are often associated with workplace violence policies.

Dr. Dietz is not a fan of zero tolerance, which provides for automatic punishment for violating a company rule. While proponents argue that the policies demonstrate resolve, provide clarity and certainty, and remove subjectivity and bias from decision making, Dr. Dietz argues that typically, zero-tolerance policies do not give management discretion, and they do not allow managers to consider personal or extenuating circumstances. “It removes the judgment from the ultimate decision maker and produces anomalies like suspending kids from school for having a squirt gun or drawing a picture of a gun, which is downright silly,” he says. “Instead what we want is not the punitive overreaction approach of zero tolerance, but rather the supportive culture of a helpful approach of ‘tell us what’s going on so we can keep everyone safe.’ And there’s lots of ways short of discipline to keep people safe when behavior is going awry. Discipline is one of the tools that will need to be used if everyone ignores the problem until it’s too late, but it’s not the first step. And as soon as you announce a zero-tolerance policy, you’re telling your employees that you regard this as a disciplinary issue, and you invite greater reluctance to report.”

Workplace Violence Standards

As of the writing of this article, OSHA announced it will pursue a federal standard aimed at preventing workplace violence among health care and social service workers. Outgoing OSHA administrator David Michaels recently wrote: “Evidence indicates that the rate of workplace violence in the health care and social assistance sector is substantially higher than private industry as a whole and that the health care and social assistance sector is growing. I believe that a standard protecting health care and social assistance workers against workplace violence is necessary.”

Dr. Dietz admits he is biased on this issue, in part because of past decisions (or lack of them) by OSHA. But mainly, he says: “There have been preventive measures available to every industry [for workplace violence] for 30 years, so OSHA is very late to the game. Instead of looking at what’s already successful, OSHA is going to create regulatory burdens that don’t get anything done, when the solutions are very simple and can be implemented for any organization in three to 12 months. Admittedly, there are some unique problems in healthcare that make that task more complex than it is for a manufacturer or a financial services company or pharmaceutical firm. While I approve their selection at which industry to look into, I shake my head at their delay in doing so, and have low expectations for the process by which OSHA will do it.”

A Global View

Rarely a week goes by without some type of workplace violence incident in the U.S. being reported in the news media. Is it just a U.S. problem?

Hardly, says Dr. Dietz. “Let’s first look at the active shooter and remember that active shooters are a very small part of the workplace violence problem. For active shooter incidents the U.S. does have more incidents, but for armed attacker incidents that difference diminishes. Part of the difference between the U.S. and other countries has to do with the prevalence of firearm ownership and availability. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing; I’m just saying that the weapon of choice in many nations is an edged weapon such as a knife or a sword, and in others it’s improvised explosive devices. So the weapons vary, and they will continue to vary, and people determined to commit a particular large-scale attack will use whatever weapon they can get their hands on. We have no reason to think there’s more of it here in the U.S. than elsewhere. The U.S. is very far ahead of the rest of the world in measuring it, caring about it, recognizing the economic impact of it and preventing it. And if we look at sexual assault in the workplace, threatening behavior in the workplace, and a host of other problems, the U.S. has already accomplished preventive work that is decades ahead of much of the world.”

The Bottom Line

Overall, Dr. Dietz wants to communicate to enterprise security executives the fact that there’s no need for an enterprise to reinvent the wheel. He suggests a comprehensive approach to deal with all types of workplace misconduct, and as an enterprise security executive, to provide the correct training for you, your team and every employee in the company.

“The worst thing for a corporate security director is that your managers don’t know when to call you and won’t call you with their concerns,” he says. “The problem today is that a very large number of misconduct instances do not get reported to security. And sometimes, even when HR officials know about it, they still don’t talk to security. Part of the way we solved that problem is by starting every training program with an interdisciplinary team that always includes HR, security, legal, IT security, compliance, communications and more.” Stressing the importance of including IT security, Dr. Dietz says: “What we often see is that the IT security people in charge of the network have a high awareness of insider threat, and they’re deploying all sorts of technical surveillance, monitoring and protection. What they’re not necessarily doing is talking to their own threat assessment team or workplace violence prevention team about detecting the behaviors among their own employees. This is all part of a bigger global issue of workplace misbehavior prevention or workplace misconduct prevention.”

Editor’s Note: For more on workplace violence, including information about how wearables and big data could bring new solutions to mitigating the problem, see page 28.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!