Smarter City Security: Mapping the Path to Success

Through partnerships, grant competitions and technology, cities nationwide are utilizing security to push their economies and quality of life forward.

Chief George Turner is a 35-year veteran of the Atlanta Police Department. The department partners with private enterprises to utilize outside security cameras, integrating them into a city-wide surveillance program for smarter policing and situational awareness called Operation SHIELD. Photo courtesy of the Atlanta Police Foundation

A few months ago, cities around the world anxiously awaited for the results of the Global Cities Index, which identifies the world’s top 125 “global” cities on the basis of their ability to attract and retain global capital, people and ideas, as well as sustain that performance in the long term.

The indexes are based on a range of metrics, each with different weighting. For the Global Cities Index, 27 metrics across five dimensions are considered: Business activity (30 percent); Human capital (30 percent); Information exchange (15 percent); Cultural experience (15 percent); and Political engagement (10 percent). For the Global Cities Outlook, 13 indicators across four dimensions were taken into consideration: Personal well-being (25 percent); Economics (25 percent); Innovation (25 percent); and Governance (25 percent).

Why does this matter? Some might say that a higher ranking means the ability for a city to grow and be economically prosperous.

Security and public safety may not be officially on the Index, but it underwrites nearly every single criteria. If a city does not have a reputation for safety, will talented, innovative people and companies be inclined to move there? If city governments are not openly invested in supporting businesses’ security and success, would capital be forthcoming? Security may be behind the scenes, but it is integral to citywide success.

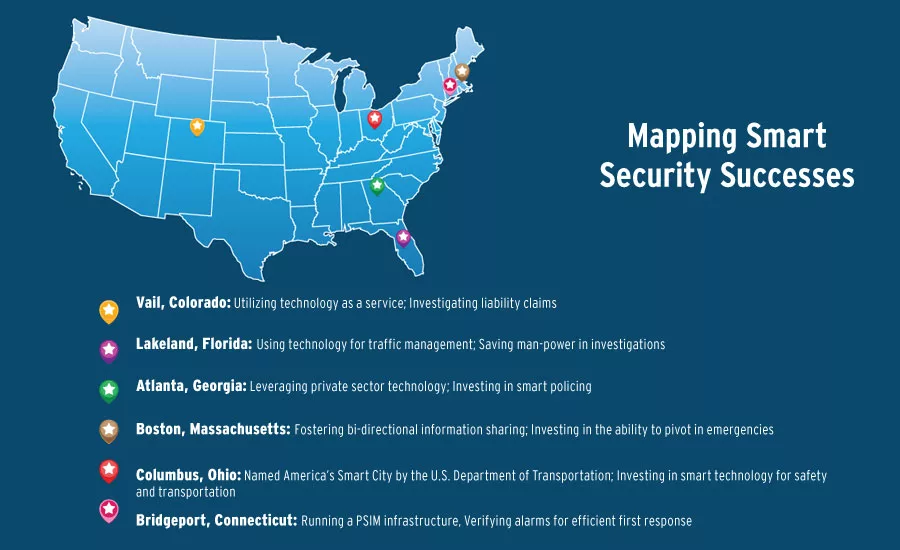

In this report, learn how city officials in the U.S. are investing in public safety, next-generation policing and smart city initiatives to improve the lives and potential of citizens, increase city security and attract global business and investment, as well as how some cities are competing for funding through a national Smart Cities search (see sidebar for information on this year’s winner).

Taking Responsibility, Sharing Data

Juliette Kayyem, who serves as a faculty member at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, teaching emergency management and homeland security and as a member of DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson’s Homeland Security Advisory Committee, says: “While we can focus on private-public partnerships, the responsibilities do not lie equally. Part of thinking about secure cities is, while there can be a lot of shared planning, the public will always view government as responsible. The good news is that the private sector is very engaged in these efforts and is a willing partner, in particular not just because they have employees, but because they are part of these communities.”

A strong example of public-private partnership success, Atlanta, Georgia, has had a tumultuous reputation for crime rates in decades past, but with current smart policing initiatives and a surge of public-private partnerships, crime rates are currently lower than they’ve been since the 1960s.

It’s also been attracting attention for its economic clout. The city has a gross domestic product of $270 billion, and it’s the third most popular city in the U.S. for Fortune 500 companies.

Atlanta Chief of Police George Turner, a 35-year veteran of the Atlanta Police Department, says that “For more than 25 years, Atlanta had a reputation as one of the most violent cities in America. I believe that because of the relationship we have through the Atlanta Police Foundation, the administration that we currently have in place, we’ve been able to foster a more cohesive relationship with business so they feel more comfortable, and so they’re relocating their business to Atlanta… Businesses are voting with their feet.”

Businesses are also helping the city improve by sharing their existing resources. Through Operation SHIELD, Atlanta police and first responders have access to more than 7,300 cameras across the city, while the city only owns and maintains about 400 of them. Operation SHIELD is a public-private partnership, through which businesses and enterprises in the metropolitan area share access to their exterior cameras with the police department, effectively multiplying law enforcement’s situational awareness without needing to multiply its budget.

“It’s clear for us that the next wave of smart policing includes data exchange, which goes from being able to communicate verbally as well as being able to view what’s going on in all quadrants of our city,” says Chief Turner. “The expenses associated with what this network would have cost us, I can only tell you what I know: In New York City, for instance in Manhattan, after 9/11, New York City received about a $300 million grant to build out a network of cameras. The City of Atlanta has now invested about $5 million on this entire network. The benefit is that we have the situational awareness that we need and in strategic locations, at pennies of the cost of other cities that are doing this nationwide as well as internationally.”

The camera feeds are viewed and monitored in the city’s Video Integration Center (or VIC), and law enforcement’s dispatchers can use the radio component of the program to share information back and forth with private security officers.

This system keeps law enforcement alert and aware, especially in large or high-profile events that cover a lot of ground. For the annual Peachtree Road Race – the world’s largest 10K, held every year on the Fourth of July – the entire route is fully recorded through Operation SHIELD, which helps law enforcement with crowd management and flow, as well as maintaining awareness of any potential threats.

“Homeland security starts with local agencies,” says Chief Turner. “No police chief in America will tell you any different. If there’s a natural emergency or hazardous situation, we will be the first on the scene. We have to be prepared and trained and working with our partners so we can respond appropriately, and find a way to build out after we make our initial response.”

For the City of Bridgeport, Connecticut, gaining situational awareness meant consolidating security systems onto one platform. According to Jorge Garcia, former Director of Public Facilities for the City of Bridgeport, and now Director of New England Operations for integration firm A-Plus Technologies, the city leveraged grants from different departments for one, unified PSIM project, rolling disparate sensors and systems into one platform in order to manage the city more effectively, Garcia says.

The system makes the city’s 1,500 cameras – including schools’ security infrastructure – and some private sector surveillance devices accessible to first responders and city officials in a more intuitive system with uniform messaging during an emergency.

For a lockdown situation in a school or city building, for example, the building can be locked down from one remote location, and the building’s doors can be unlocked from one remote location. Personnel in the security operations center can send 3D maps and information about the building and environment to first responders so they’re better informed about the situation they’re entering. If there’s a fire alarm in the high school, Garcia says, an operator could log into the building’s security system and use the surveillance cameras to verify the presence of smoke, helping to inform first responders that it’s an active event, not a potential false alarm.

The City of Bridgeport is not finished yet. Because it’s running with a PSIM infrastructure, there’s no technical ceiling to how many systems or devices could be added, so private sector enterprises can join in, and more cameras can be added when funds are available.

Bi-directional information sharing is key to so many public-private working relationships in cities across the world. According to Alan Snow, Director of Safety and Security for the Boston region of real estate investment trust Boston Properties: “There are multiple private-public sector partnership networking groups where our security team has been regularly participating and in many cases actually facilitating the networking meetings to exchange information and provide further information sharing via group emails. Additionally, our security team conducts regular orientation and familiarization tours of our properties for first responding public safety officials, including police, fire and EMS, to enable efficient and effective response to routing incidents, as well as major emergencies such as active shooter, mass casualty and fire conditions.”

Snow and the Boston Properties security team also participate in joint tabletop exercises with public safety agencies and other private sector companies. Snow also cites the importance of partnering outside a single municipality or jurisdiction to include local, state and federal agencies, advocating for a “proactive approach along the lines of an overarching Meta-Leadership framework” that focuses on enhancing communication, crime prevention and emergency preparedness coordination, as well as mitigating potential threats and major emergencies, by taking a holistic view. Learn more about Meta-Leadership from the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative at

npli.sph.harvard.edu/meta-leadership.

He says that these holistic city security initiatives “provide the basis for an overall resiliency strategy for the city, the residents and the private enterprises by creating robust community service liaison programs through which direct channels of communication are established for bi-directional communication between the private sector and public safety. Once these channels are established, information about crime trends, quality of life issues, suspicious activity reporting and real-time emergency and safety information can be disseminated. They provide an opportunity to enable invaluable networking, build relationships and collaboration, while at the same time establishing familiarization and trust before an emergency event occurs.”

Snow also references the use of technology, such as sharing video feeds or utilizing social media for easier information sharing with citizens and private enterprises.

City Services and Amenities

For many cities, smart security hinges on technology, and oftentimes, private sector technology will provide ways of making security less burdensome and more beneficial to the city and its citizens.

In the City of Lakeland, Florida, city officials found unexpected benefits and opportunities when they standardized their disparate security systems into Genetec’s Security Center platform, putting video surveillance, access control, intrusion alerts and license plate recognition systems in one program, installed at 53 sites throughout the city, including police and fire departments, city hall, the regional airport, public works facilities and others, managing a total of 650 cameras and more than 450 doors.

According to Alan Lee, Security and Safety Systems Supervisor for the City of Lakeland’s Public Works Facilities department, the system is constantly being reviewed and revamped to bring new technology and new benefits for the city. Currently, he is working to add license plate recognition (LPR) technology to make meter management and law enforcement tasks more efficient. Soon, patrolling officials will be able to access the system via mobile devices. The system also helps parking enforcers to establish citations more quickly.

The system is also integrated into all traffic signal cameras, so city personnel can use the system to effectively monitor and maintain the flow of traffic and helping to detour drivers around accidents. “This also allows our local police department to tie in and view those same cameras, so for special events downtown, it helps to point out any abnormalities. It helps keep citizens safe and secure behind the scenes.”

“We’re also adding LPR technology onto the system for our downtown parking enforcers,” Lee says. “You have limited parking time, to free up parking for other individuals. This technology can read license plates faster than a person on foot can and more accurately, establishing those citation or alarms much quicker.”

In the ski resort city of Vail, Colorado, city officials were looking for a way to improve security and awareness for the World Alpine Ski Championships in 2014. Because the terrain is sometimes challenging to lay fiber in, the city used Siklu’s wireless radios to extend surveillance services further out.

According to Vail’s Director of Information Technology, Ron Braden, the town’s 140-camera system could be tied into law enforcement’s security programs during events, heightening situational awareness. The system was used to locate suspicious vehicles or track individuals during the event, but now, traffic officers utilize the cameras for loading and delivery monitoring, and public safety officials can use the system to investigate crime and potential liability, in the event of a staged slip-and-fall or similar incident.

“This helps Vail from a loss standpoint; it helps public safety for investigations, and it helps to improve the guest experience,” says Braden. “Anytime you have a big event coming into town, you need to be able to support them, both from a bed standpoint and an infrastructure standpoint. The special event organizations that come into town use our infrastructure, they use the WiFi, they use the camera systems – we do a lot of crowd monitoring, from a traffic control and crowd monitoring standpoint, and the cameras really come in handy.”

Intelligence and All Hazards

Last month, a French parliamentary committee examining the two terrorist attacks in Paris presented 40 proposals, in which the lawmakers urged the government to merge some of France’s overlapping – and sometimes competing – agencies to create a new national agency, similar to the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, to set up a shared anti-terrorism database, to better monitor prisons for radicalization, and to tighten the sentencing of convicted terrorists. The committee raised questions about the efficiency of the state of emergency that French President Francois Hollande declared following the attacks in November, and of the deployment of 10,000 soldiers around the country to protect cities and other sensitive areas.

The committee cited that several of the terrorists involved in the attacks were flagged as potential threats or as radicalized militants in other European nations, but this information was not shared with the French police. While it didn’t disavow the use of physical security technology, states of emergency or law enforcement patrols, the report called for a greater focus on intelligence-gathering and sharing.

According to Kayyem, “Resiliency is not just a mood. It’s investment in key areas, and one of those is investment in the capacity to pivot. In homeland security planning now, we don’t actually talk about terrorism specifically. We don’t talk about climate change specifically. We don’t talk about cyber threats specifically. We talk about all hazards planning. And the reason why is, in this age of globalization, you can’t know what the specific threat may be, but what you do know is if something bad happens, our public safety apparatus is going to have to pivot to respond.”

In the 2013 Boston Marathon, she says, there was a public health apparatus, and before the bombing, they were concerned about blisters, exhaustion and dehydration. “It was their capacity to pivot, which was investments in training, equipment and exercises, that turned them into essentially a war triage unit, and the success of that is measured in this fact: Three people died in the Boston Marathon because of the explosion. Not a single person died who made it to a hospital. That’s remarkable.”

According to Snow, “The partnerships and individual relationships had already been established prior to the Marathon Attack, and as a result, the response and dissemination of information after the attack was more efficient and effective. The experience and collaboration between the private sector and public safety after the attack resulted in an enhanced strengthening and re-affirmation of the criticality for the existing partnerships. Participation from a few additional private enterprises and public agencies increased due to their recognition of the benefits and that they need to be more involved in advance and on a regular basis.”

Kayyem adds that security initiatives, while important, can’t stop a city from functioning, such as adopting airport-level security screening for New York City subway stops. City security officials should assume a consistent and persistent level of risk, and focus on how to respond and mitigate the consequences of potentially exploited vulnerabilities, she says. Because if a city’s security team is solely focused on terrorism and then the impact of the Zika virus comes their way, gaps in security could easily arise.

In Atlanta, Chief Turner works with the city’s Emergency Preparedness Officer and public safety departments to collaboratively develop cohesive plans in response to a variety of scenarios, such as a citywide evacuation. City leaders hold tabletop exercises with public response officials and local, state and federal partners, including the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, Georgia Municipal Association and the FBI, as well as Federal partners at the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, local university security officials, and public transit authorities, such as MARTA.

After major events, the team works to develop appropriate responses and training, adjusting existing procedures where necessary. After the terrorist attacks in Paris, for example, the city started offering active shooter response training for businesses and communities, Chief Turner says.

“All the tabletops that we can train for will never be all-inclusive. We have to continue to adjust our policies, our procedures and our training techniques so we can mitigate what’s being pushed out there in front of us,” he adds.

Managing Traffic,

Managing Security

The smart management of traffic and smart parking initiatives will save 4.2 billion man-hours annually by 2021 – equivalent to one working day per driver per year, according to Juniper Research’s study Worldwide Smart Cities: Energy, Transport & Lighting 2016-2021. The report notes that the establishment of viable public transportations to replace private vehicle use, in addition to millions of smart parking spaces, will service to improve private and commercial vehicle flow.

According to research author Steffen Sorrel: “Facilitating the movement of citizens within urban agglomerations via transport networks is fundamental to a city’s economic growth. Congestion reduces businesses’ competitiveness, and contributes to so-called brain-drain.”

On the forefront of this smart city movement in Columbus, Ohio. Winner of this year’s U.S. Department of Transportation Smart City Challenge – a Silicon Valley-style bid for $40 million in DoT funding, plus a wave of private sector investment – Columbus is working to improve the lives of its citizens through technological advancement and thoughtful deployments to help both its economic center and its underprivileged neighborhoods.

Columbus’s Smart City team will deploy solutions in four districts: residential, downtown, commercial and at the city’s cargo-dedicated airport. But it was Columbus’s people-first proposal that gained attention. The city plans to install street-side mobility kiosks, a new bus-rapid transit system and smart lighting to increase pedestrian safety and access to healthcare for traditionally underserved areas and neighborhoods.

According to Aparna Dial, Director of Energy and Sustainability at The Ohio State University and project head for Smart Columbus, the goal of this project is to improve opportunities for success for all residents.

For citizens in the Linden Neighborhood, a low-income area with poor access to amenities, jobs, banks and healthy food options, safe, reliable transit is absolutely essential to improving quality of life. Currently, the area has few transit shelters, intersections with high crash rates and low street lighting. In addition, due to low access to healthcare services, this neighborhood has four times the national average rate of infant mortality.

The Smart Columbus project will bring in smart street lighting with efficient LED lights, connected by WiFi – which will also be available for citizens to use for free. Crosswalks and transit stops will feature pedestrian detection technology. They plan to install traffic signals that communicate with vehicles so signals can adjust in real-time to the needs of commuters, as well as changing to clear the way for first responders. The signals will also be able to be controlled manually by city management officials to clear the way for evacuations or emergencies.

“At the end of the day, we need to remember that this is about moving people up the ladder of opportunity, moving people forward,” says Dial. “Lack of transportation options really traps people into a cycle of poverty with little or no options to escape. I feel that it’s our responsibility to provide reliable, affordable transportation to all families – families of color, low-income families – because that helps broaden their access to quality education and decent housing and good jobs… these are all essential elements of the American dream. Everyone has a right to follow that dream.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!